Thyroid disease has some symptoms in common with certain mental health conditions, this is especially true for depression and anxiety.

Thyroid disease has some symptoms in common with certain mental health conditions, this is especially true for depression and anxiety.

Sometimes thyroid conditions are misdiagnosed as these mental health conditions.

This can leave you with symptoms that may improve but a disease that still needs to be treated.

The relation between thyroid function and depression has long been recognized.

Patients with thyroid disorders are more prone to develop depressive symptoms and conversely depression may be accompanied by various subtle thyroid abnormalities.

The relationship between stress and the thyroid is not clear. The number of people who cite unusually stressful experiences before the onset of hyperthyroidism seems to bear out the theory of stress as a precipitating factor.

While others can come through the same upheavals without developing thyroid disease, some perhaps are predisposed to it.

On the other hand, it can be argued that the illness itself, before its symptoms are manifested, is contributing to the situation of stress.

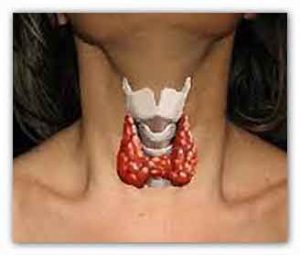

The thyroid gland produces hormones that regulate basal metabolic rate, the speed at which our bodies burn food for energy.

The thyroid gets its directions from the hypothalamus, at the base of the brain, by way of the pituitary gland.

On a signal from the hypothalamus, the pituitary sends thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) into the bloodstream.

It travels to the thyroid gland and causes the release of thyroxine (T4), which is partly converted into triiodothyronine (T3).

Through a feedback mechanism, the hypothalamus determines when levels of T4 and T3 are low and alerts the pituitary to supply more TSH.

In a person with hypothyroidism, the thyroid gland does not fully respond to TSH, so levels of T3 and T4 remain low while TSH accumulates in the blood.

Depressione

The most common cause is an autoimmune disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, but the symptoms can also result from an infection, from cancer, or from treatment of an overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) with surgery, radiation, or medications.

An underactive thyroid can lead to progressive loss of interest and initiative, slowing of mental processes, poor memory for recent events, fading of the personality’s colour and vivacity, general intellectual deterioration, depression with a paranoid flavour, and eventually, if not checked, to dementia and permanent harmful effects on the brain.

Hyperthyroidism is a condition characterized by an overactive thyroid: a review of the literature estimates that up to 60 percent of people who have hyperthyroidism also have clinical anxiety while depression occurs in up to 69 percent.

Traditionally, the most commonly documented abnormalities are elevated T4 levels, low T3, elevated rT3, a blunted TSH response to TRH, positive antithyroid antibodies, and elevated CSF TRH concentrations.

Hyperthyroidism (particularly Graves’ disease) affects people of all ages, with symptomatology including restlessness and inability to focus, weight loss, tachycardia, heat intolerance, diaphoresis, and diarrhea.

People with an overactive thyroid may exhibit marked anxiety and tension, emotional lability, impatience and irritability, distractible overactivity, exaggerated sensitivity to noise, and fluctuating depression with sadness and problems with sleep and the appetite.

In extreme cases, they may appear schizophrenic, losing touch with reality and becoming delirious or hallucinating.

In instances of each condition, some persons have been wrongly diagnosed, hospitalized for months, and treated unsuccessfully for psychosis.

It is very important for the physician to explore fully and give the tests for thyroid dysfunction, which today are relatively simple.

The physician must also be careful to check the thyroid in cases where psychiatric medications must be taken over a long period.

Lithium, the drug commonly used to stabilize the moods and increase the efficiency of manic-depressives, can cause hypothyroidism, particularly in middle-aged vulner: the side effect is not universal and happens only after long-term use.

The hypothyroidism in its turn can produce depression, the very problem that the treatment was intended to relieve.

This underscores the importance of regular monitoring of thyroid function during long-term lithium therapy.

Mental disorders merge highly with thyroid diseases.

Because of its regulatory effects on serotonin and noradrenalin, T3 has been linked closely to depression and anxiety.

It has known that in many cases, the mental symptoms persist even after normalization of thyroid function by treatment.

Psychosocial factors including stress have been associated with mental symptoms even after thyroid function normalization in Graves’ disease and a combination of mental disorders have been related to the exacerbation of hyperthyroidism.

Recent studies suggest that psychosocial factors including emotional stress are related to the onset of Graves’ disease.

Winsa et al. reported the first large population-based case-control study demonstrating a relationship between stress and Graves’ disease.

208 (95%) of 219 eligible patients with newly diagnosed Graves’ disease and 372 (80%) of all selected matched controls answered an identical mailed questionnaire concerning marital status, occupation, drinking and smoking habits, physical activity, familial occurrence of thyroid disease, life events, social support and personality.

Compared with controls, Graves’ disease patients claimed to have had more negative life events in the 12?months preceding the diagnosis, and negative life-event scores were also significantly higher (odds ratio 6·3, 95% confidence interval 2·7-14·7, for the category with the highest negative score).

When the results were adjusted for possible confounding factors in a multivariate analysis, the risk estimates were almost unchanged.

These findings suggest that psychosomatic approaches based on the bio-psycho-social medical model are important for the treatment of mental disorders associated with Graves’ disease.

For more information

Thyroid Foundation of Canada

The Thyroid and the Mind and Emotions/Thyroid Dysfunction and Mental Disorders

Link…

Journal of Thyroid Research

The Link between Thyroid Function and Depression

Link…

Harvard Health Publishing

Thyroid deficiency and mental health

Link…

Journal of Clinical & Translational Endocrinology

Graves’ disease and mental disorders

Link…

Strong Ties Between Thyroid Disease, Mental Health in Kids

Link…

Pediatrics

Mental Health Conditions and Hyperthyroidism

Link…

MDN

This post is also available in:

Italian

Italian