|

About one of every three adult Americans currently

have hypertension, yet a surprising number don’t

know they have it and less than half have their high

blood pressure under control—leading many health

experts to refer to the condition as a “silent

killer”.

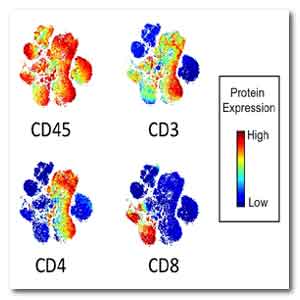

IMAGE: Four types of immune T cells from an adult

with normal blood pressure cluster on a CyTOF map.

Source: Meena Madhur, Vanderbilt University School

of Medicine, Nashville

For many folks, blood pressure control can be

achieved through lifestyle changes, such as losing

weight, exercising, limiting salt intake, and taking

blood pressure medicines prescribed by their

health-care provider.

Unfortunately, such measures don’t work for

everyone, and some people continue to suffer damage

to their kidneys and blood vessels from poorly

controlled hypertension.

Meena Madhur, a physician-researcher at Vanderbilt

University School of Medicine, Nashville, wants to

know whether the immune system might be playing a

role, and whether this might hold some clues for

developing new, more targeted ways of treating high

blood pressure.

To get such answers, this practicing cardiologist

will use her 2016 NIH Director’s New Innovator Award

to conduct sophisticated, single-cell analyses of

the immune systems of people with and without

hypertension.

Her goal is to produce the most comprehensive

catalog to date of which human immune cells might be

involved in hypertension.

Back in the 1960s, animal studies provided the first

indication that the immune system might play a role

in hypertension.

But with a relatively limited set of tools available

then to explore the immune system, limited progress

was made over the ensuing few decades.

Then, thanks to advances in knowledge and technology

arising from the genomic revolution, that line of

inquiry began to move forward about a decade ago,

starting with more sophisticated studies on the role

of immunity and inflammation in hypertension,

focusing on genetically engineered rodents.

Now, Madhur is taking the next step with a research

project focused on humans.

To date, she and her colleagues have collected blood

samples from a pilot group of 39 adult volunteers—23

with hypertension and 16 without.

These groups are carefully matched for age and body

mass index (BMI), two strong risk factors for

hypertension.

To get the data, her group will work with Vanderbilt

colleague Jonathan Irish, an expert in Cytometry by

Time-of-Flight (CyTOF) technology, who will assist

in panel design, validation, and data analysis.

CyTOF is a form of mass cytometry in which

individual antibodies are labeled in the lab with

heavy metal tags for visualization, instead of the

customary fluorescent tags.

This gives Madhur more channels to work with than

fluorescence flow cytometry, allowing her team to

pack a lot more antibody markers onto each cell,

thus increasing the chances of finding something

interesting.

CyTOF has been used in cancer studies and to monitor

a type of immune T cell that is affected by the

human immunodeficiency virus, the cause of AIDS.

In the Accelerating Medicines Project (AMP), it’s

also being used to look at immune cells in biopsies

from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.

But CyTOF has never been applied on such a

comprehensive scale to monitor the immune system in

hypertension.

Irish has developed a computer software program that

employs machine learning to map similarities in the

antibody markers attached to the millions of immune

cells processed from the blood samples.

Each dot plotted on the map represents an individual

cell, and the dots cluster into distinct islands of

T cell subsets, B cell subsets, and innate immune

cells.

The more distance between each dot, the more

dissimilar their molecular characteristics are.

According to Madhur, flow cytometry allows you to

find what you are looking for, while CyTOF allows

you to find what you never knew existed.

Madhur will look for any unique clusters of cells on

the map that come only from people with

hypertension.

If so, she will pick out eight to 12 features from

those cells that will allow isolation by traditional

flow sorting and then further characterize these

cells in vitro.

She will also follow up on her initial leads by

opening her study to more volunteers with a wider

range of BMIs and age to determine if hypertension

associated changes in the immune system track with

aging and obesity.

For more information

U.S. National Institutes of Health

Link...

MDN |